How do you speak to someone broken by the deepest pain imaginable? What words do you pick to echo across their canyon of wounds? Can you shout over the noise of their waterfalls of grief without sounding like you're yelling? Without deserting them to merely self-comfort through paperboard platitudes, awkward jokes or the abandonment of a change of topic?

These are the questions rattling around my mind as I try to formulate a useful discussion about the treatment of victims of rape as reported in the media lately. If you don't know the recent stories, here is a summary:

Many girls and women (and boys, and sometimes men) are being been raped all over the world. In two cases, some teens and some adults reacted by not just minimizing, nor even merely blaming, but actively threatening and attacking the teenage victims. In response one young girl committed suicide. Another younger girl tried, twice.

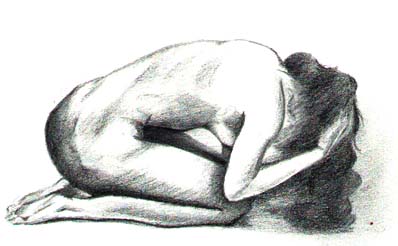

It's hard, formidably challenging, to express the depth of injury and pain caused by rape to someone who has not experienced it. Words can't frame the concept easily. This survivor art from Survivorsartfoundation.org does a good job:

Many girls and women (and boys, and sometimes men) are being been raped all over the world. In two cases, some teens and some adults reacted by not just minimizing, nor even merely blaming, but actively threatening and attacking the teenage victims. In response one young girl committed suicide. Another younger girl tried, twice.

It's hard, formidably challenging, to express the depth of injury and pain caused by rape to someone who has not experienced it. Words can't frame the concept easily. This survivor art from Survivorsartfoundation.org does a good job:

|

| Chains, Candyce Brokaw |

|

| The Infant, Leslie Kursh |

|

| Pauline in the Thorn, Rebecca Lange |

If you are a victim of rape, you have probably thought about suicide. Maybe even tried it. Or you may have instead (or also) sought slow-death, like drinking yourself into liver-failure, driving drunk, shooting heroine, licking X tabs from strangers, having unprotected sex with numerous risky partners, eating compulsively into obesity, living on the streets, cutting.

This may have been because, as soon as the rape was over, part of you immediately knew how bad it was. You knew you were on a long road. You knew your rape wasn't just a physical injury, like a bruise or cut that would quickly fade. It left a mental scar. Somewhere inside of you it created a rip that wouldn't close up. Like a skin tear, left gaping, that easily accumulates infection.

Even if your conscious mind "left" (via unconsciousness or dissociation) your body knew, recording the attack forever.

Clinically, rape is a trauma that triggers the animal trauma response in baser parts of the brain than the conscious mind. That trauma response, if prevented from completing (by the continuance of fear, shame or other overwhelming emotions) can lead to post traumatic stress. That stress, that tear, if left untreated over time (especially in children) can become chronic and elaborated into dissociative disorders like DID; anxiety disorders like phobias or OCD; mood disorders like depression, manic depression and rageaholism; and sexual disorders like nymphomania. Rape can severely diminish victims' capacities and quality of life for months, years, sometimes decades after the event. Sometimes for the rest of their lives.

And this is not a subject for debate. The only people questioning whether rape is harm are men who've never been raped. Their musings are about as valid as mine on the demands of dancing at the Bolshoi Ballet.

A broader problem is society's wonderings about whether rape is really that harmful. Whether the harm done to perpetrators or those accused of perpetration with all this sorrow is, perhaps, not worse. The Onion recently ran a keen spoof video on this. This line of reasoning is, itself, very painful for victims. Victims already know, powerfully, that they alone cannot always protect themselves. When suddenly everyone in the world appears to join a perpetrator's "team," a victim can feel profoundly abandoned, helpless and vulnerable.

So why does this happen? Why do bystanders to rape so often react this way?

Well, without writing a Wikipedia page on the topic (though it may be too late to avoid that), first (IMO) I think this happens because, ironically, people focus too much on whether harm is done. Let me explain.... If we think the severity of our crimes is dictated by the amount of harm we inflict, then we will think that if our victims haven't experienced too much harm, then our crimes aren't that bad. We don't think about us, the kind of people we are, who we are becoming.

If we stay in this line of thinking, our desire to be innocent, to avoid consequences or to shy from the discomfort of acknowledging horrific crime can naturally propel our logic into its next step.... If we are only as guilty as our victims are harmed, and if their potential lack of harm means we're not guilty, then maybe there's a way to see them as not that harmed. Maybe it really wasn't that bad. And so maybe we're not that bad. In fact, maybe they're the bad ones for telling us we are.

And then this becomes a cultural thought.... It would be awful if people could be hurt so badly. And if people can be hurt so badly, then that means people can do terrible things. And if people can do terrible things, maybe we can do terrible things, or at least maybe we consented to them, or could have prevented them but didn't. Maybe we could have helped, but failed. But then maybe people aren't really harmed that badly, and so maybe people aren't really capable of inflicting that much harm. And if that is true, then we haven't failed to stop anything, or help anyone who really needed it. Maybe everything's okay. And in fact maybe it's the people who claim things are not okay who are really in the wrong.

But everything is not okay. And thinking it is okay is how little girls die.

Most men (almost all?) want to protect girls and have an instinctive disgust of men who prey on girls. A child molester is, to most men, a freak of human nature and deserves to be forever publicly humiliated, as a warning to the others. But whatever might happen between a young woman (no longer a “girl”) and a young man is a completely different subject.

ReplyDeleteI really like "The Infant" - Great post

ReplyDeleteHi Jessy ~ I know, so moving. A very accurate portrait. Thanks for reading. Be blessed ~ The Curator

ReplyDelete